Want to become an instant expert in our filmmaker of the month without committing yourself to an entire filmography? Then you need the Hell Is For Hyphenates Cheat Sheet: we program you a double feature that will not only make for a great evening's viewing, but will bring you suitably up-to-speed before our next episode lands…

ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN (1976) and THE PELICAN BRIEF (1993)

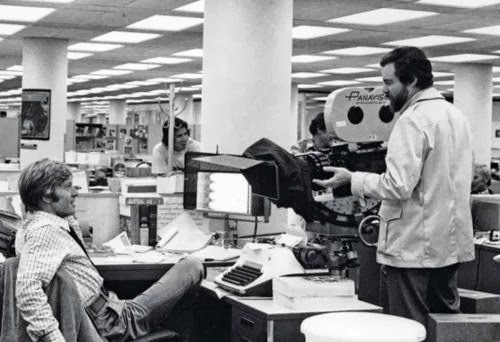

We said this in the episode announcement, but we'll say it again: Alan J Pakula was cinema's poet laureate of paranoia. His filmography is consumed with conspiracy thrillers both real and imagined, and sitting high atop that mountain, and high atop the canon of really all cinema, is All the President's Men. The ink wasn't dry on Nixon's resignation when this film hit cinemas, and perhaps it's that lack of perspective that helped keep it from becoming an overt rallying cry. There is not a moment of sentiment in this procedural ode to investigative journalism, and it remains the gold standard of rewatchable, engaging, relevant cinema. And look, nothing can possibly follow it, so you should probably just watch it twice. Or, alternately, take a swing at The Pelican Brief. We're not necessarily recommending this because it's also a great work; more because it helps define the second overwhelming sphere of Pakula's career. The song remains the same - government conspiracies, massive cover-ups, terrifying parking garages - but the style is a world away, as Julia Roberts's law student teams up with Denzel Washington's journalist to run away from bad guys with guns as they shine a light on a conspiracy that goes all the way to the White House. These films may look similar if you're squinting at a one-line synopsis, but they are, in more ways than one, chalk and cheese. And that's exactly why they make the perfect double if you want to get your head around Pakula in one easy viewing.

Substitutions: If you can't get or have already seen All the President's Men, seek out The Parallax View (1974). If not for President, Pakula would likely be remembered as the guy behind The Parallax View, a brilliantly understated work of paranoia. This time we're watching a fictitious threat, but told with the same verisimilitude as his Watergate-based follow-up. If you can't get or have already seen The Pelican Brief, get your hands on Presumed Innocent (1990). The Harrison Ford thriller is arguably the baseline for the legal thrillers that came to dominate the 1990s; it's very possible that Pelican author John Grisham was himself bitten by a radioactive Presumed Innocent. It's also the first of Pakula's '90s polyptych of highly-stylised thrillers, and would, whether intentionally or unintentionally, set the tone for the remainder of his career.

The Hidden Gem: Want to see something off the beaten path, a title rarely mentioned when people talk about the films of Alan J Pakula? Then you should track down Sophie's Choice (1982). Before you protest and claim that Sophie's Choice is actually mentioned quite often, ask yourself this: is it the film itself that everyone refers to, or the title, which through standard pop culture overuse has become the rote go-to phrase that refers to any mildly aggravating choice, from deciding New Year's Eve plans to choosing between sandwich condiments. If you've not seen it, the film is nothing like its reputation; surprisingly light and far from the unrelentlingly bleak prospect many believe it to be. Give it a spin. You might be surprised.

The next episode of Hell Is For Hyphenates, featuring Alex Ross Perry talking the films of Alan J Pakula, will be released on 30 June 2018.

Want to become an instant expert in our filmmaker of the month without committing yourself to an entire filmography? Then you need the Hell Is For Hyphenates Cheat Sheet: we program you a double feature that will not only make for a great evening's viewing, but will bring you suitably up-to-speed before our next episode lands…

Want to become an instant expert in our filmmaker of the month without committing yourself to an entire filmography? Then you need the Hell Is For Hyphenates Cheat Sheet: we program you a double feature that will not only make for a great evening's viewing, but will bring you suitably up-to-speed before our next episode lands…

Want to become an instant expert in our filmmaker of the month without committing yourself to an entire filmography? Then you need the Hell Is For Hyphenates Cheat Sheet: we program you a double feature that will not only make for a great evening's viewing, but will bring you suitably up-to-speed before our next episode lands…

Want to become an instant expert in our filmmaker of the month without committing yourself to an entire filmography? Then you need the Hell Is For Hyphenates Cheat Sheet: we program you a double feature that will not only make for a great evening's viewing, but will bring you suitably up-to-speed before our next episode lands…